Ahdie Rasouli, a primary school teacher in Dandenong, is an inspirational testament to the power of resilience, determination and passion. After fleeing Afghanistan with her mother and siblings in early childhood, Ahdie experienced exclusion and discrimination in Iran before moving to Australia at 9 years of age. It is this childhood hardship, in part, which has inspired Ahdie to become a teacher who empowers students from diverse cultural backgrounds and who advocates for the importance of education. While matters have improved, Ahdie says that students are still facing adversity every day: “we have to understand them”.

As a single mother with four young children, Ahdie’s mother sought refuge from Afghanistan in Iran. However, as refugees the family was not accepted in their new country. Unable to attend school in Iran as a refugee student, Ahdie recalls once being kicked to the back of the line in a local bakery because she was Afghan, in a blatant show of exclusion that is difficult for a child to understand. “Mum struggled”, she says, with not only working long days to support her children, but also home-schooling them. Eventually, when Ahdie was 9 years old, the family was sponsored to move to Australia.

“We didn’t know what to expect. We had no relatives or friends in Australia, and we didn’t speak any English at all”, says Ahdie of the move, which was both a hopeful and daunting prospect. Laughing, she recalls how the Australian embassy had pictures of tigers on the wall, so naturally her three siblings became excited to see tigers roaming around the outback. The reality, of course, was very different to the family’s first perception.

Initially, Ahdie and her family settled in Springvale. For 5 months, she says life was quite difficult; none of them knew English, and there was a distinct cultural disconnect with the local population of central Asian migrants, with whom they shared no common language. At school, Ahdie was bullied for wearing the hijab, and pleaded with her mother to move back to Afghanistan. “I cried a lot. I didn’t want to go to school – it made life really hard for Mum”, she explains, remembering feeling “out of place” in that community.

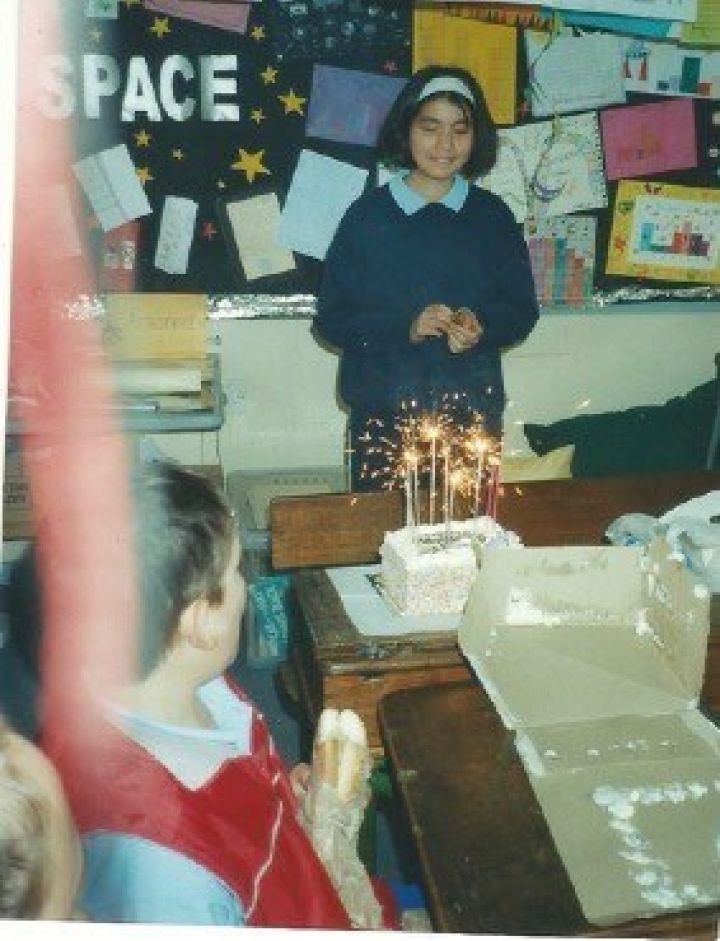

Seeing her children unhappy in Springvale, her mother moved them to Dandenong North, where they knew of two other Afghan families. While she still felt “odd” in Australia, it was a much more multicultural area, and at her primary school the teachers and students were “smiling all the time”. Ahdie says the Dandenong North Primary School “shaped who I am”, with staff going above and beyond to make everyone feel included regardless of their background. The ESL program was a turning point in Ahdie’s life in Australia. With other refugee children in the class she “felt at home”, and she was able to actively participate in classes once she had a firm grasp on the English language. Ahdie says the overwhelming support of the school was epitomised on one cold morning: when a teacher asked Ahdie and her siblings to put a jumper on and discovered they didn’t own any, he drove them to Dandenong market himself to buy some for them.

Serendipitously, Ahdie is now a CRT teacher at her beloved Dandenong North Primary School. It has grown since she was a student there herself, but “the love is still there!”. To start her career path, Ahdie studied at Australian Catholic University in Melbourne. She speaks of her experience with some fellow students who couldn’t understand the need for inclusion in teaching, who would ask, “why should we make changes for refugee or Aboriginal students in the classroom?”. At first, she says this was frustrating. Then, deciding to combat these non-inclusive attitudes, she shared her experience as a refugee student with her tutorial class, which was “raw and difficult and empowering”. Even today, Ahdie hopes that by having these difficult conversations with people she can show them a different perspective on life, and help them to realise their privilege.

As a school with a majority of students from migrant or refugee backgrounds, Ahdie marvels at the palpable love and passion of the teachers at Dandenong North Primary. Their drive and commitment to fostering an inclusive classroom is “incredible”, she says: “everyone has their own problems, but [at Dandenong] we all put masks on to make each day great for the students – and not all teachers are capable of that”. She loves her job; her passion lies in the “cute, innocent moments” of speaking to young students, joking with them to ensure they feel included, and striving to make her classroom feel like home. Ahdie says simple things like normalising students’ packed lunches – where some may have a sandwich, some may have curry – can make a huge impact, and demonstrate from a young age that “being different is a strength”. She is also a strong believer that “kids are our future”, and that making a small positive difference now could mean a big difference in the future in terms of diversity.

The coronavirus pandemic period has been a whirlwind for Ahdie, who gave birth to her second child exactly two weeks before this interview, during Melbourne’s first lockdown. Ahdie lives with her two children – one newborn, and one 2.5 year “energetic” toddler – along with her husband and mother, and says that amongst the hardship of the pandemic, it has been a “blessing” to have the family all at home together. She says in normal times, she may have felt guilty asking for support with the newborn, so having the extra helping hands and constant company as her husband works from home is a true silver lining.

In terms of teaching during lockdown, Ahdie has been on maternity leave, but has heard varied opinions on remote learning from her colleagues. Some teachers are enjoying the forced flexibility and extra time with family that remote teaching affords, while others are stressed about the lack of control when teaching in a virtual classroom. As Ahdie says, “it’s not a time where you can be a perfectionist”, and she encourages people to just do their best to get by in these exceptional circumstances. Most importantly, teachers must acknowledge that some students will be struggling more than others, and prioritise the mental wellbeing of those who may have a harder home life and less access to internet. “At the moment, we must all let go on the learning side of things, and that’s okay,” she says. Jokingly, with parents and caregivers needing to take a more active role in their children’s learning during lockdown, Ahdie notes she is glad to see more widespread recognition for teaching as an “underrated” profession which requires immense patience and expertise. At the end of the day, she says “there is always a bright side, even in this negative situation”.

To find out more about the fantastic work of teachers like Ahdie at Dandenong North Primary School, click the link below for the award-winning documentary ‘Talk for Life’.

Let us know!